"That's the man! I'll never forget that face!"

Unreliable Eye Witness Testimony

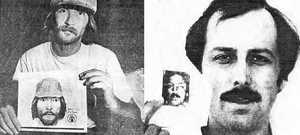

The men on the left and right were picked out of police lineups by victims of rapes and robberies committed by the man in the middle.

Fortunately for Mr. Kruska, pictured on left, his resemblance to the composite drawing of a slaying suspect only led to his being detained. Walt Sweeny, pictured on right, wasn't as lucky. He was put on trial for robbery. The jury acquitted him of all charges.

The most common cause of wrongful convictions in our judicial system is mistaken identification.--U.S. Dept. of Justice Study. See 46 cases were faulty eyewitness testimony put people on death row.

In the 1984 case of People v. McDonald, the California Supreme Court unanimously held that:

"Dr. Shomer ... has taught numerous courses on the psychology of perception, memory, and recall, and has spoken and written frequently on such topics in both medical and legal settings. He is conversant with the scientific literature on the psychology of eyewitness identification, has done experimental research on the subject himself, and has published articles on that research. He has qualified as an expert psychological witness in more than two dozen state and federal trials. [Now over 250]. The People do not question the witness' qualifications.

When an eyewitness identification of the defendant is a key element of the prosecution's case but is not substantially corroborated by evidence giving it independent reliability, and the defendant offers qualified expert testimony on specific psychological factors shown by the record that could have affected the accuracy of the identification but are not likely to be fully known to or understood by the jury, it will ordinarily be error to exclude that testimony. Not all psychologists, of course, have the special knowledge, experience, or training to qualify as experts on psychological factors affecting eyewitness identification. In the case at bar, Dr. Shomer's relevant expertise was both demonstrated by defendant and impliedly conceded by the prosecution."Click here for the full text of People v. McDonald.

Factors to consider in proving identity by eye witness testimony.

- The opportunity of the witness to observe the alleged criminal act and the perpetrator of the act;

- The stress, if any, to which the witness was subjected at the time of the observation;

- The witness' ability, following the observation, to provide a description of the perpetrator of the act;

- The extent to which the defendant either fits or does not fit the description of the perpetrator previously given by the witness;

- The cross-racial or ethnic nature of the identification;

- The witness' capacity to make an identification;

- Evidence relating to the witness' ability to identify other alleged perpetrators of the criminal act;

- Whether the witness was able to identify the alleged perpetrator in a photographic or physical lineup;

- The period of time between the alleged criminal act and the witness' identification;

- Whether the witness had prior contacts with the alleged perpetrator;

- The extent to which the witness is either certain or uncertain of the identification;

- Whether the witness' identification is in fact the product of [his] [her] own recollection;

- Any other evidence relating to the witness' ability to make an identification.

How Often Does The Criminal Justice System Get It Wrong?

By Roger Roots February 5, 2001

The late great Learned Hand was one of the most knowledgeable judges to ever serve on the American bench. He served as chief judge of the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals and composed more than 2,000 legal opinions. No one could know better than Judge Hand how accurate the American legal system was as a mechanism for discovering criminal guilt. In 1923, Hand wrote an opinion in a New York criminal case indicating that American court procedures had for too long been “haunted by the ghost of the innocent man convicted.” “It is an unreal dream,” concluded Hand. “What we need to fear is the archaic formalism and the watery sentiment that obstructs, delays, and defeats the prosecution of crime.”

Judge Hand was not alone in this assessment. Experts agree that the rate of wrongful conviction in American courts is exceedingly low. Huff, Rattner, and Sagarin, authors of the 1995 book Convicted but Innocent, spent more than a decade studying the persistence of wrongful convictions, gathering evidence and assessments from police administrators, sheriffs, prosecutors, public defenders, and judges. The three scholars concluded that about 0.5 percent of persons convicted of felonies are estimated to be innocent of the crimes convicted of. This rate amounted to 10,000 innocents per year in 1995 when there were only one million people behind bars (today there are over two million). Convicted But Innocent shocked the criminal justice system and brought complaints from official experts that the three academics had drastically overstated the rate of wrongful conviction.

But DNA has blown the lid off of even the extravagant assessment of Huff, Rattner, and Sagarin. DNA analysis has suggested that all of the experts-wise judges like Learned Hand, dedicated police officers, liberal academics, and hard-working lawyers on both sides of the bar-have all underestimated the rate of wrongful conviction. Last year’s best-seller Actual Innocence by Barry Scheck, Peter Neufeld and Jim Dwyer suggested the true rate of wrongful convictions may be closer to ten percent than to one-half of one percent. DNA tests used before trial have exonerated at least 5000 prime suspects out of the first 18,000 DNA suspect samples at the FBI and other crime labs-suggesting a pre-trial error rate of more than 25 percent. Since 1977, some 553 people have been executed in the United States while another eighty death row inmates have been released after they were found innocent. For every seven executed, one innocent person is freed-an “error rate” of more than twelve (12) percent. In the State of Illinois, 12 people have been executed since 1977 while 13 have been released after proving their innocence-an error rate of 52 percent. Last year the Governor of Illinois-who supports the death penalty-finally called a moratorium on the use of the death penalty until all of the quirks in the process are ironed out.

But the quirks in the death penalty process are, if anything, less pronounced than the quirks in the criminal justice system generally. The true error rate for the criminal justice system as a whole may be much higher than the twelve percent national error rate in death penalty cases. DNA analysis is only available where a DNA specimen exists, such as in rape cases or bloody murder cases. For the vast majority of innocent criminal defendants, there is no hope of exoneration through DNA analysis.

Even if the true error rate of America’s criminal justice system is only ten percent, this translates to 200,000 innocent people presently behind bars in the United States. It means that there are more innocent prisoners in America than there are prisoners of all kinds in France, Germany and Britain combined. It means that the present number of innocent American prisoners is actually higher than the entire American prison population back in 1970.

Moreover, even the guilty are often wrongfully convicted. Too many convictions are owed more to the zeal of the justice system than to appropriate evidence. Improperly obtained evidence, coerced or inaccurately taken confessions, and exaggerated testimony have become common elements in the criminal courts. It is the totally “clean” prosecution, rather than, as Learned Hand suggested, the totally innocent person convicted, that is too often the anomaly in the criminal justice system.

Those who think that improper tactics are excusable in the quest to convict the guilty have contributed to the conviction and incarceration of large numbers of the truly innocent. The revelations owed to DNA analysis should serve as a wake up call for a system in dire need of overhaul. Blackstone’s ancient reminder that it is better to let ten guilty men go free than to convict a single innocent person should operate as the highest operating principle of American justice. All of us-jurors, police officers, lawyers, judges, public officials and scholars-should renew our commitment to the idea that wherever a shadow of a doubt exists that a person might be innocent, all errors should be on the side of caution.

Roger Roots - Founder,

Providence, Rhode Island

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

The Exercise Of Power Is The Fastest Acting Intoxicant Known To Man.

You Can Get Drunk Before You Know It.

Many times the reason or purpose for events in our life initially escapes us,

but I am certain we can find reason and/or purpose in everything that happens!

It takes a short time to learn to exercise power, but a lifetime to learn how to avoid abusing it.

We are no longer a country of laws, we are a country where laws are "creatively interpreted."

Sniff Around This Site!

OR

Search Rhode Island Criminal Database or

RI Supreme Court Opinions & Orders